Data protection as a human right

*This is an AI-powered machine translation of the original text in Portuguese

More than 4 billion people are currently connected to the internet, constantly providing their data and metadata indiscriminately to those who know how to use them. The exponential use of data in online and offline environments has brought the topic of data protection to the forefront over the last decade. This issue gained special attention in the media following Edward Snowden's revelations about the surveillance techniques employed by the United States through the National Security Agency ("NSA") and the scandal involving the misuse of Facebook user data by Cambridge Analytica.

The concept of data protection has traditionally been linked to the concept of privacy, a right recognized internationally as a human right, at least since the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1945. However, despite the clear influence of data protection on the daily lives of individuals around the world, human rights courts still hesitate to recognize data protection as part of this fundamental set of guarantees[1].

In Europe, for example, Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights guarantees the right to private and family life. Despite its somewhat vague designation, the European Court of Human Rights ("ECtHR") has used the doctrine of the right to privacy under Article 8 in cases involving unwanted photos, confidentiality of correspondence, and even the correction of the names and genders in the records of transgender individuals.

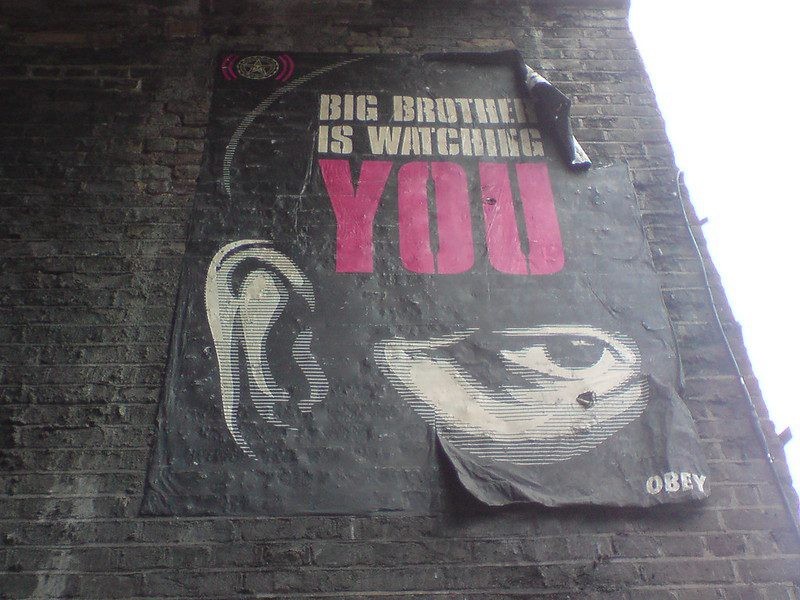

In landmark cases like Big Brother Watch v. the U.K., the ECtHR had the opportunity to recognize data protection as a fundamental human right and include it in the list of rights under Article 8. The background to the Big Brother Watch case is the well-known scandal revealed in 2013 by Edward Snowden involving the actions of the U.S. government and the NSA.

Snowden's revelations went beyond exposing improper investigation and monitoring techniques used by the NSA. Snowden indicated that other security agencies, such as the Government Communications Headquarters ("GCHQ") in the UK, also employed potentially illegal surveillance methods.

In this regard, in Big Brother Watch, it was up to the ECtHR to assess the legality of information sharing between the NSA and GCHQ, as well as the British government's ability to intercept the communications of its citizens on a massive scale. However, the European Court's approach turned out to be more cautious than expected by scholars and activists in the field, as it did not directly address data protection.

The connection between the facts of this case and the privacy of the individuals involved is evident, as there was constant monitoring by the NSA. Many people around the world were monitored without suspicion of violating the law or judicial oversight to mitigate abuses. Moreover, beyond mere monitoring, there was improper sharing of this information with third-party security agencies like GCHQ.

In the background, one can even see a connection between the actions of the NSA and GCHQ and issues related to the structures of modern democracy. The surveillance actions of security agencies disrupt the balance of power between states and their citizens. As stated by the ECtHR in the judgment of the Big Brother Watch case, there is a risk that a secret state surveillance system could destroy a democratic regime under the false pretext of protecting it (Big Brother Watch v. the U.K., §308). However, the Court did not directly address the correlation between privacy, personal data, and democracy.

The correlation between democracy and human rights is widely explored by international courts and specialized doctrine. It is recognized, for example, that the right to participate in free elections is a human right. Specifically, the American Convention on Human Rights guarantees the full exercise of political rights, including "freely elected representatives," "free expression of the will of the voters," and "general conditions of equality" when running for public office.

In parallel, and still under investigation, the facts uncovered in the Cambridge Analytica scandal have the potential to demonstrate an even greater connection between data protection, human rights, and democracy, as the personal information of many Facebook users was used to influence political campaigns around the world.

As the use of personal data continues to increase, it is expected that human rights courts will develop doctrines and jurisprudence capable of recognizing the importance of personal data protection, acknowledging it as a human right derived from privacy and the right to a truly democratic regime.

In July 2019, the ECtHR agreed to reconsider the Big Brother Watch case, referring it to the Grand Chamber. With the review of the current decision, it is expected that the Grand Chamber will address both the improper use of personal data and the potential impact of the misuse of personal data on democratic regimes.

[1] Due to the limited scope of this work, the possible reasons for Human Rights Courts' reluctance to recognize data protection as a human right, as well as the potential consequences of such recognition, will not be addressed. These topics will be addressed in other works at an appropriate time.

*Co-authored with Juliana da Cunha Mota. Originally published in JOTA.