Gender discrimination in the era of Big Data and Artificial Intelligence

*This is an AI-powered machine translation of the original text in Portuguese

International Women's Day is, above all, a milestone in the fight for rights. The issues that were established in the past, such as pay and job equity, respect for women's sexual and reproductive freedom, and the fight against feminicide, still hold relevance today. However, in addition to historical issues, this struggle now takes on new dimensions in the era of Big Data and Artificial Intelligence (AI). Thus, new challenges emerge in the context of digitalization and the platformization of societies, and for this reason, it is important to discuss the future of women and the fight for equality in the digital age.

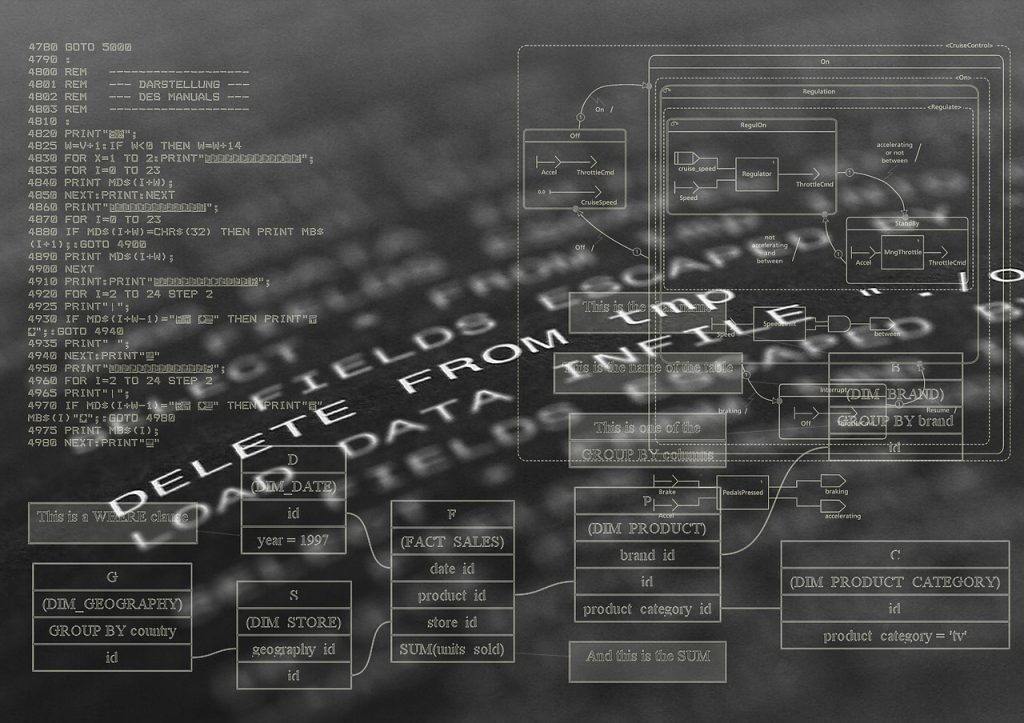

Concrete situations in the job market, financial services, or healthcare already demonstrate how AI can act with discriminatory biases. In other words, how AI can reinforce prejudice against women and undermine decades of progress in gender equality.

This doesn't happen because AI is inherently bad or flawed, but because it learns from data collected in a complex and sometimes unequal world. Therefore, the information that feeds machine learning systems (the foundation of AI) can be loaded with preconceptions, such as gender stereotypes. These stereotypes, in turn, may not accurately represent important aspects of women's lives or even lead to erroneous inferences resulting in discriminatory decisions in automated systems.

According to the Gender Gap Report[1] from the World Economic Forum, the overwhelming majority of AI professionals are men, representing 72% of the workforce in 2020. In tech giants like Facebook[2], 37% of positions are held by women. In Microsoft[3], this percentage drops to 28.6%. Considering that the architecture of AI systems is designed by people, and the data used to train these systems is also selected, it is important for tech companies and professionals to consider gender issues when developing their products and systems. This necessarily involves including more women in this discussion.

The shortage of women in this industry can lead to implications in the design of many products, as they may incorporate the perceptions of their developers, perpetuating patriarchal stereotypes in technologies, such as subservience associated with the female personality in digital assistants[4].

One of the technologies involved in training these digital assistants is Natural Language Processing (NLP), which allows machines to understand and reproduce human communication with its various linguistic variables. However, studies show that NLP can incorporate gender biases present in the data that AI uses to learn associations, for example, associating "computer programmer" with a man and "homemaker" with a woman[5].

Similarly to what happens with NLP, gender discrimination can also be present in image generation algorithms.

MIT Technology Review published a report showing that 43% of the time when algorithms completed the image of a man, he was portrayed wearing a suit. When receiving photos of women, 53% of the time, the algorithm completed them wearing a bikini[6].

The result was reproduced even when the woman in question was a notable politician, such as U.S. Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. One of the concerns expressed in the publication is the impact these algorithms can have on women's lives. If this type of bias is employed in high-impact decisions (such as AI-driven pre-selection in recruitment based on video analysis, including image and language analysis), what could be the consequences for female candidates?[7]

This concern about gender discrimination in AI-based candidate selection is not limited to video analysis algorithms and unfortunately is not hypothetical. In 2017, a major international retail company abandoned AI-based recruitment software because the technology was manifestly biased against female candidates[8].

The tool had been trained based on resumes received by the company over a ten-year period. Since the technology industry is predominantly male, most of these resumes were from men. Therefore, the AI recognized male candidates as preferable and began downgrading female resumes.

There are other examples of the reproduction of societal discrimination through machine learning in various areas and to the detriment of minorities. To name a few, there are cameras that identified people of Asian descent as blinking in photos; an image auto-tagging system that identified a black couple as gorillas; low efficiency in facial recognition for women and especially for black women; among others.

In this way, two main ways in which stereotypes (gender or otherwise) can be incorporated into machine learning are identified. Through the design of the architecture or through the data selected to train the AI. In the cases mentioned regarding digital assistants, for example, the discussion is about incorporating gender stereotypes into technology development. In other cases, biases were embedded in the databases used to train AI, which learned to reproduce these biases in their automated operations.

The high potential for impact that AI presents has led various global organizations, such as the European Commission[9] and the OECD[10], to develop ethical principles to guide the development of these technologies. Some common factors in these principles include privacy and data protection, transparency, and fairness. However, critics point out that references to gender equality and female empowerment in existing principles are scarce[11].

It is important for the technology sector to remain vigilant about gender issues. This perspective should come from various angles, including ensuring diversity in product development teams, testing for cognitive biases, and transparency in their processes. Specifically, based on the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), data processing repeatedly carried out in the development of Artificial Intelligence must respect the guiding principles of the legislation, especially non-discrimination and accountability.

[1] Available at: http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2020.pdf. Accessed on February 22, 2021.

[2] Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/311827/facebook-employee-gender-global/. Accessed on February 22, 2021.

[3] Available at: https://www.thestatesman.com/technology/women-now-represent-28-6-microsofts-global-workforce-1502931069.html. Accessed on February 22, 2021.

[4] UNESCO, "I'd Blush if I Could: closing gender divides in digital skills through education," March 2019. Available at: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000367416.page=1. Accessed on February 24, 2021.

[5] Sun et al., "Mitigating Gender Bias in Natural Language Processing: Literature Review." Available at: https://www.aclweb.org/anthology/P19-1159.pdf. Accessed on February 24, 2021. Other references: Caliskan et al., "Semantics derived automatically from language corpora contain human-like biases." Available at: https://science.sciencemag.org/content/356/6334/183. Accessed on February 24, 2021.

[6] Available at: https://www.technologyreview.com/2021/01/29/1017065/ai-image-generation-is-racist-sexist/. Accessed on February 24, 2021.

[7] The technology referenced in the MIT Technology Review article is from the company HireVue. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2019/10/22/ai-hiring-face-scanning-algorithm-increasingly-decides-whether-you-deserve-job/. Accessed on February 24, 2021.

[8] Source: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-amazon-com-jobs-automation-insight/amazon-scraps-secret-ai-recruiting-tool-that-showed-bias-against-women-idUSKCN1MK08G. Accessed on February 25, 2021.

[9] European Commission, "Ethics Guideline for Trustworthy AI," 2019. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/news/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai. Accessed on February 25, 2021.

[10] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, "Recommendation of the Council on Artificial Intelligence," 2019. Available at: https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/OECD-LEGAL-0449. Accessed on February 25, 2021.

[11] UNESCO, "Artificial Intelligence and Gender Equality – Key findings of UNESCO’s Global Dialogue," 2020. Available at: https://en.unesco.org/AI-and-GE-2020. Accessed on February 24, 2021.

*Coauthored with Ana Catarina de Alencar. Originally published in JOTA.