Does it make sense to regulate data centers for AI in Brazil?

*Originally published in JOTA.

**This is an AI-powered machine translation of the original text in Portuguese.

The tremendous “hype” around artificial intelligence and the attention it has been receiving in international media have fueled the enthusiasm of legislators in Brazil, as evidenced by a series of proposals aimed at regulating different facets or implications of the technology. The main bill is PL 2338/2023, recently approved by the Senate and currently under discussion in the Chamber of Deputies.

Alongside it, there are bills intended to regulate the use of AI tools for managing and maintaining data in the SUS (PL 1522/2024), the ownership of inventions autonomously generated by AI systems (PL 303/2024), and to require AI companies to make available tools that allow authors to restrict the use of their content by algorithms (PL 1473/2023).

These bills are primarily concerned with the impacts of AI applications in various fields on individual rights or collective interests.

However, among all these initiatives, PL 3018/2024 stands out, as it focuses on the processing infrastructure for the development and application of AI systems—that is, data centers.

Confusion Between Hardware and Software

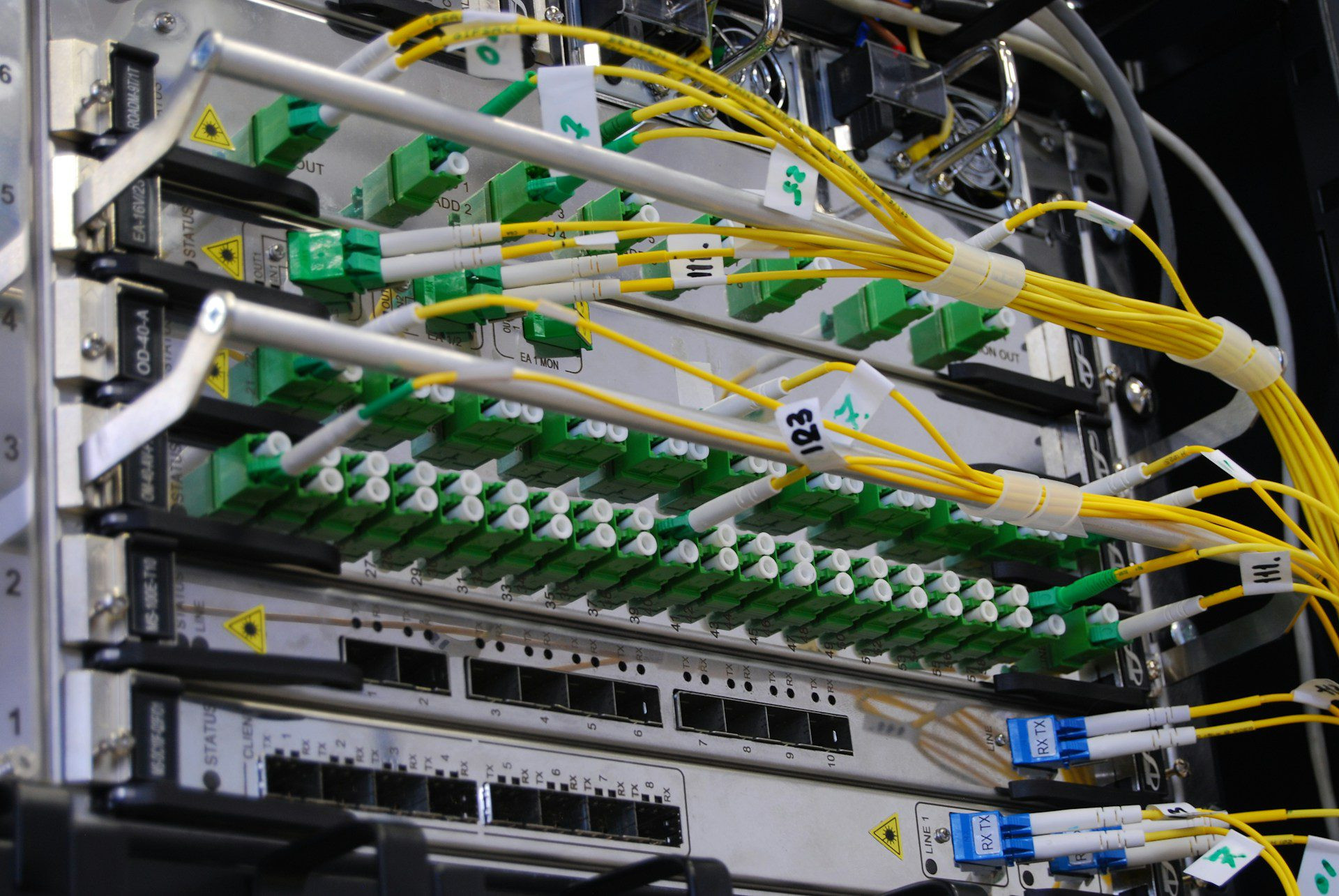

The new regulatory drive already stems from a fundamental confusion between the physical level, i.e., hardware, and the programming level, i.e., software of IT systems. Data centers correspond to the physical layer composed of hardware; their purpose is to receive and store data and to provide the computational capacity infrastructure for its processing.

The operator of a data center in the strict sense (i.e., one that does not act as an AI company owning its own infrastructure) has no role in programming and operating the software—that is, in determining which data, of what type, and for what purpose are processed. This control lies with the AI development company or the operator of AI systems that use the data center to process inferences or task requests with the data inputs.

Thus, it makes no sense to impose obligations on the data center operator related to controlling the purpose of data use, or regarding the responsible use of AI to mitigate risks arising from the application of these systems, such as transparency obligations regarding the use, the data, and the operated AI model. This issue is already discussed in PL 2338.

Similarly, the obligation to “ensure the privacy and protection of personal data, in accordance with the LGPD” (Art. 3, II) would only make sense if limited to requiring adherence to the best practices in data or cyber security; however, such an obligation is already contained in item I of the same article, which assigns the operator the duty to “ensure the physical and cyber security of the data stored and processed.”

It also makes no sense for the infrastructure provider to conduct audits to verify whether its clients’ use of data complies with the law. Data interoperability and portability also pertain to the prerogatives and limitations of data holders regarding the exercise of third-party rights over that data—in other words, they do not relate to hardware.

The same reasoning applies to data governance obligations, as the data center is neither the controller nor the operator, nor the AI developer. Appointing a data protection officer, conducting impact assessments, or managing sensitive data are also misplaced, except for specific aspects of cyber security, which, in relation to personal data, are already covered by the LGPD.

Which Data Center?

The bill regulates objects that do not yet exist in Brazil—data centers entirely dedicated to AI. Specialized debate forums, along with the governmental authorities involved in the subject, project that the operation of these structures will become feasible within a three- to five-year horizon, given the enormous requirements of these data centers in terms of storage capacity, power distribution, and connection speed.

But even if this is a fairly forward-looking regulation, it would be necessary to specify which data centers are being addressed—and it only makes sense if they are infrastructures with high data processing capacity—otherwise, smaller data center operators that do not process AI would be unfairly subjected to legal obligations.

For instance, in the “Strategy for the Implementation of Public Policy to Attract Data Centers,” a document published by the Ministry of Development, Industry, Commerce and Services (MDIC), although not dealing exclusively with AI, strategic data centers for Brazil are defined as those classified as Tier3 (International Standard), focusing on colocation and high density (more than 7 kva per rack).

However, the bill does not establish criteria regarding volume, security, availability, or redundancy to classify the data centers that are truly relevant and justify the creation of governance rules by law, which may make the application of the regulation extremely costly for data center operators that do not operate at that scale.

Which Law?

The law does not establish sanctions in the event of non-compliance with its provisions. Article 7 merely refers, without further details, to the sanctions present in “existing legislation.” But to which laws does the bill refer?

It’s one of two scenarios: either it does not establish new obligations—thus merely reinforcing that the sanctions for obligations in other laws should be applied when violated—or the bill establishes new obligations, the non-compliance with which could not lead to punishments provided for other types of conduct.

This ambiguity is also notable in that the text does not specify which authority would be responsible for monitoring the compliance with its obligations, which could later create both positive and negative inter-agency conflicts.

Which Regulatory Model?

The bill proposes an intrusive regulation, in contrast to the responsive model that is increasingly debated in the Brazilian regulatory environment. There are no mechanisms provided to incentivize operators who comply with the established obligations.

In the European Union, for example, the Data Centers Code of Conduct does not create binding obligations but rather establishes voluntary standards applicable to companies that adhere to sustainable technologies and energy efficiency. Participants are subject to the best practices defined in the document and the respective audits, and those who demonstrate a significant reduction in energy consumption are eligible for financial incentives.

Brazil, with its predominantly renewable energy matrix, has a unique advantage: its ability to offer a clean and abundant energy infrastructure, ideal for the installation of large data centers. In a time when sustainability and energy efficiency have become essential requirements for technological development, this characteristic is a valuable asset that should be highlighted in regulation, not neglected.

AI regulation in Brazil should serve as a channel to promote the growth of a technological ecosystem that leverages the country’s renewable energy sources. Only in this way will it be possible to create a competitive, sustainable, and innovative environment, capable of attracting major developers and positioning Brazil at the center of green AI production and processing.

Conclusion

In its eagerness to be a pioneer in AI regulation, the data center bill presents a problematic example, typical of regulatory carelessness. The text reveals a clear lack of understanding of the subject of regulation and imposes overlaps with other legislation, in addition to creating obligations that do not pertain to data center operators but rather to developers and software operators, generating legal uncertainty.

This represents a significant failure, as it misses the opportunity to create an environment that encourages investments in technologies focused on energy efficiency and “green AI,” a strategic area for the country’s future.