AI regulation: a way out of the impasse between developers and authors

*Originally published in Correio Braziliense.

**This is an AI-powered machine translation of the original text in Portuguese.

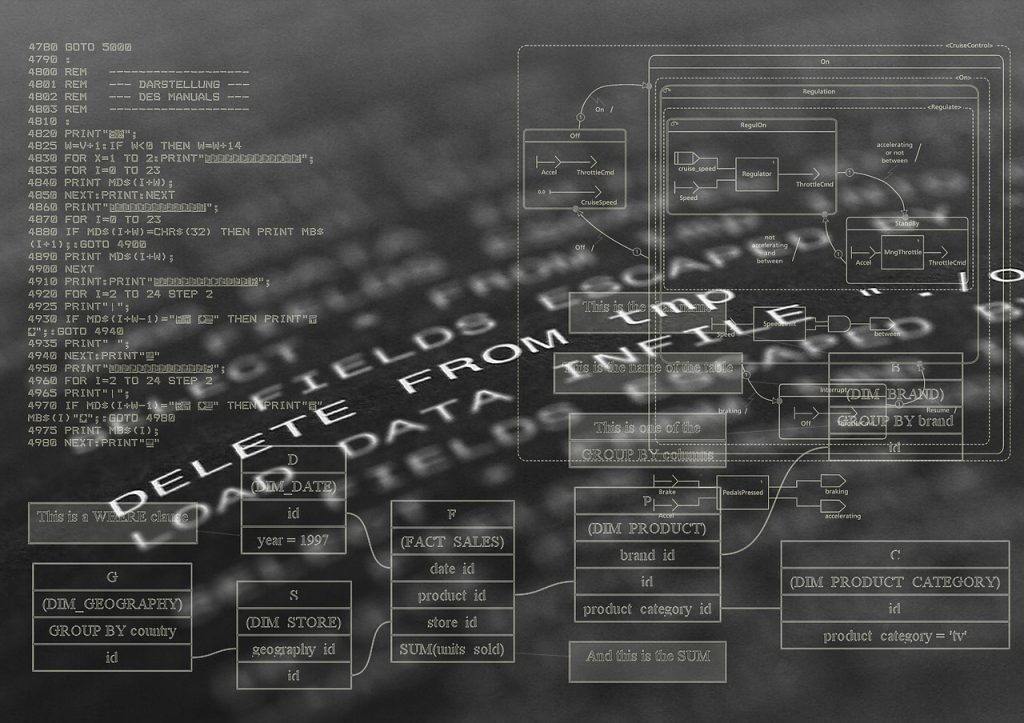

Copyright has become the most controversial point surrounding the Artificial Intelligence Bill (PL 2338/23), currently under discussion in the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies, with opposition, on one side, from AI system developers concerned with removing barriers to innovation, and, on the other side, from authors seeking remuneration for the use of their works in the development and application of Generative AI systems.

Both claims are valid and desirable. Would it be possible to reconcile them?

Not with the approach adopted in the current text, inspired by European legislation, which bases the proposed remuneration on compensating the author for the use of protected works in the training of Generative AIs. The text provides for the obligation of developers to list the protected works used, the prohibition on using them against the express will of the authors (the so-called “opt-out”), and the obligation of remuneration resulting from such use already at the training stage, with an exception for use in scientific activity.

The issue is that copyright infringement for the use of works in AI training is controversial and is currently being debated in national and foreign courts. The point is that copyright protection concerns the exploitation of the author’s individual expression in the specific work, whereas training seeks to extract patterns—such as styles and concepts—into a mathematical model representing the aggregate of works used for training. In other words, the work, as data subject to statistical analysis, is not truly exploited as a work during the training stage of AIs.

If, in the past, the concern was to compensate for the high cost of authorship amid the constant reduction of reproduction costs, AI brings a new challenge: the reduction of the cost of intellectual production itself. This requires a new equation. Furthermore, copyright protection is atomized in the individual work, while the technology operates in aggregate form, making it impossible to identify the individual contribution of each work to the construction of the model.

But the main problem lies in the focus on obligations during the training phase, which generates financial costs: identifying each protected work (in the sweep of online content) and managing authorial consent. These costs would be incurred even without any revenue resulting from the commercial exploitation of the system, and they do not take into account the fact that only a fraction of the experimentation necessary for innovation yields results.

Added to this is the difficulty of setting values and interpreting exceptions by the courts, something already observed in Europe and which generates legal uncertainty. Such costs may lead major foreign developers to simply stop using national literary and artistic production when developing their models, which could result in undesirable digital colonialism—unless Brazilians can and are willing to pay significantly more for an AI developed in Brazil with national authorial content. A very high bet.

We are facing a new technology that generates value and creates a new form of consuming cultural content—an interactive consumption in which the user can adapt content assisted by AI tools. This has the potential to expand the market for authors, and there are several reasons to remunerate them that do not rely on the alleged infringement of individual authors’ rights.

First, for distributive justice. Without the production of human authors, there would be no AIs capable of simulating that production. If authorial work is part of the value chain as a necessary input for the technology, it is fair to remunerate it. Second, because Generative AI competes with human production at extremely low cost, with the potential to undermine it. Third, because literary and artistic production must be fostered for its value in integrating and shaping our culture and as a vehicle for aesthetic values and social criticism. Fourth, because AI developers themselves need human content.

What is the solution? Completely remove the burden on AI system training, requiring only the indication of the provenance or sources of the data used, and base remuneration to the collective body of authors—or to cultural production—on a proportional and appropriate share of the revenue obtained by developers and distributors from Generative AI systems that have the potential to compete with human intellectual production.

This is not about compensating for the exploitation of individual works. It is about the fair distribution of value obtained in the production chain through the extraction of cultural styles, concepts, and patterns, to be directed to collective management organizations responsible for remunerating authors and promoting programs to incentivize literary and artistic creation. The objective burden on revenue may make Generative AIs more expensive due to cost pass-through in licensing, but this would have the beneficial effect of balancing competition between human production and AI-assisted or AI-generated production, addressing, in the equation, the challenge posed by the reduction of production costs.

And copyright protection is not excluded for the outputs of these systems, that is, not during training but when users employ them in a way that individualizes works for commercial purposes, which falls to the courts under copyright law.

With this, copyright finds its proper object of application by the courts in the use of AI systems; national intellectual production is protected and encouraged with a new source of remuneration; national developers have room for experimentation and innovation; and national cultural production does not risk being excluded from technologies consumed by Brazilians.