*Originally published in Jota.

**This is an AI-powered machine translation of the original text in Portuguese.

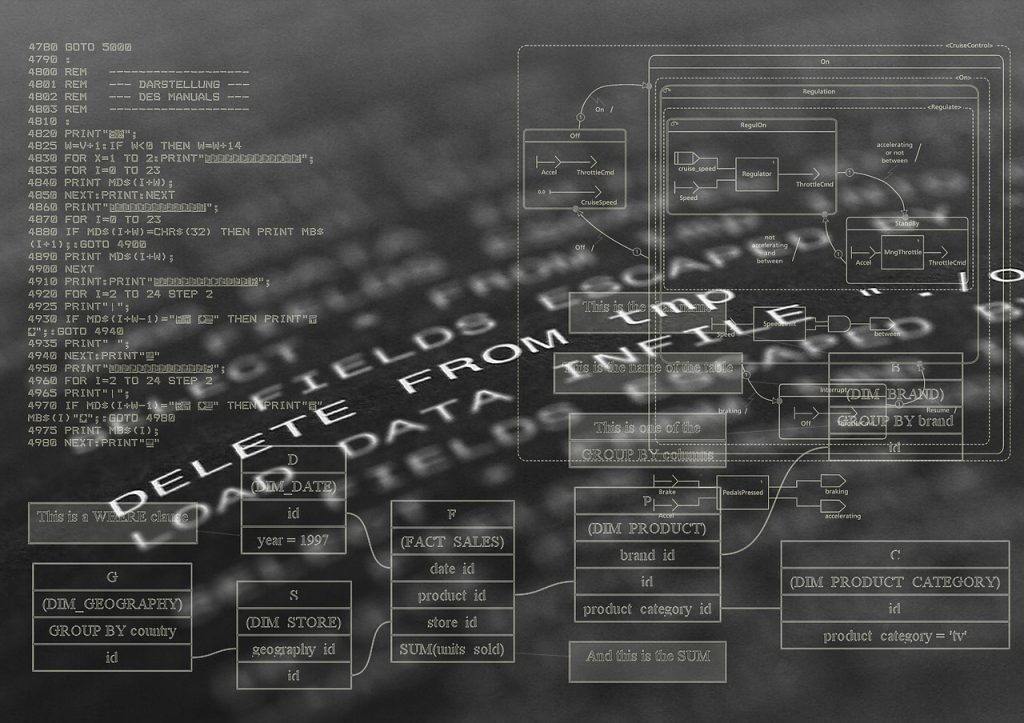

At the ceremony that enacted the so-called Statute of the Digital Child and Adolescent, the government submitted to Parliament Bill 4675/2025, aimed at regulating competition in the so-called “digital markets,” which denotes a set of different markets related to online services such as social networks, search engines, audio and video streaming, app stores, marketplaces, and so on.

The bill, drafted based on a study conducted by the Ministry of Finance, targets agents that may have not only economic power but also “systemic relevance” in those markets.

Although the concept is not precisely defined, the focus is on companies that, in addition to having a minimum global revenue of R$ 50 billion or R$ 5 billion in Brazil, may control access to users and to strategic personal and commercial data across multiple interrelated digital services.

To address this concern, the bill proposes expanding the powers of CADE (the Administrative Council for Economic Defense) not only to punish anti-competitive behavior but also to establish certain obligations and prohibitions on commercial conduct for selected companies, even before such conduct takes place (ex-ante) — therefore, without the need to establish actual harm — and regardless of any consideration of potential efficiencies or benefits to end consumers resulting from the practice.

In other words, conduct by a company designated as systemically risky becomes, in antitrust terminology, prohibited per se, except in cases where it can be justified by information security concerns or by improvements to the functionality of the “ecosystem” relative to other players in complementary or interconnected services.

The motivation for moving beyond the traditional ex-post model of repressing infractions in digital markets, according to the Ministry of Finance’s study, stems from the difficulty of developing a “theory of harm” under traditional antitrust methodology and the excessively long analysis periods. As a result, the existing tools are deemed incapable of addressing positions consolidated by decades of dominance by large technology companies — a dominance resulting from structural factors that create barriers to new entrants, as well as new types of conduct capable of restricting the development of competitors. It is emphasized that the goal is not to act against digital companies because of their “size,” but rather because of the technical, structural, and behavioral problems identified in that study.

However, the focus on what has occurred in recent decades introduces certain symptoms, within the bill’s text, that could negatively affect the national economy.

The main one is the ten-year designation period, during which an entity identified as having “systemic relevance” remains subject to the imposed obligations and prohibitions on its conduct. This duration seems out of step with the recent pace of market dynamics, which has seen, in less than five years, the rise of innovative companies whose products have grown exponentially — such as TikTok among social networks, ChatGPT, and the Chinese online retail platforms Temu and Shein — all of which have exerted strong competitive pressure on market leaders across different digital services.

Particular attention should be given to generative AI, which cannot be seen merely as a tool to enhance existing digital services: it is a disruptive force that challenges previously consolidated markets. One example is the proliferation of AI-powered search engines targeting the market long led by Google, prompting it to integrate generative AI features into its services. Adobe Photoshop, in turn, has been significantly challenged by image-generation tools such as Midjourney and Stability AI and responded by developing its own generator.

Ride-hailing platforms are already being pressured by the advance of autonomous vehicles and are investing in that technology, while AI personal assistants threaten various websites and marketplaces. As these assistants can process the information available on the internet to provide personalized recommendations, they could, in theory, reduce the need for multi-click searches and navigation, thereby undermining the advertising-based model that is currently central to the sector’s business strategy.[1]

The assumption that AI markets will be dominated by the current leaders in digital services — an assertion jointly made last year by the European, U.S., and U.K. antitrust authorities[2] — seems disconnected from the evidence. Not only are the supposed barriers of computing capacity, expertise, and data access being eroded by innovation, but AI markets also lack the features that raised concerns about concentration in digital markets: there is no near-zero marginal cost, no network effects, and the data feedback loop is limited, as it depends on quality rather than quantity and is not based on the targeted advertising model that exploits personal data.[3]

This ongoing and fast-paced disruption makes the ten-year designation period seem utterly unreasonable and raises doubts about the adequacy of other provisions contained in the bill.

First, the designation is based on non-cumulative criteria — meaning that, for instance, a company with vertical integrations in adjacent markets and access to large amounts of personal data could be designated, creating significant potential for “false positives” in assessing systemic risk. This concept encompasses not only already established companies, captured by a “backward-looking” approach, but could also, if we fail to “look ahead,” constrain new players that have, as noted above, brought “systemic benefit” rather than systemic risk.

Second, the bill lists types of conduct that CADE may specify as mandatory or prohibited for designated entities. These include not only potential infractions, such as prohibitions against discrimination or access restrictions, but also so-called “remedies” for anti-competitive behavior.

In other words, it includes obligations related to transparency and pro-competitive measures, such as data portability or interoperability, without requiring CADE to demonstrate the proportionality of these measures in relation to competition concerns. Including remedies among the list of obligations could effectively turn CADE into a true regulator of the digital environment — with significant discretionary power — rather than solely an authority for the repression and prevention of anti-competitive practices.

Regulatory interventions in markets characterized by such a degree of innovation, as is the case with digital markets in the face of AI, may prove counterproductive. A recent example is CADE’s initiation of merger review procedures (APACs), still pending and approaching their first anniversary, concerning partnerships between digital services and AI startups.[4]

CADE, inspired by a measure adopted (and soon abandoned) by the UK competition authority, considered that such partnerships might represent a new version of so-called “killer acquisitions,” in which acquisitions of innovative entrants by dominant firms went undetected as potentially anti-competitive by regulators.[5] However, these partnerships have in fact been a major driver of differentiation and competition in AI markets, with positive spillover effects even on digital services themselves.[6] CADE’s scrutiny of these partnerships, without prompt resolution, could generate legal uncertainty and discourage such pro-competitive arrangements.

Finally, one procedural aspect stands out. The bill proposes a process lasting at most 365 days for designation and another 365 days for conduct specification — which may occur simultaneously. Within this timeframe, the period allocated for formal defense opportunities totals only 45 days, which seems unbalanced.

The most important issue, however, is the absence of mechanisms for adjusting conduct through agreements. Given all the nuances of digital markets, it is possible that, in different contexts, modifying a company’s behavior in what is deemed potentially harmful could resolve the issue without undermining potential benefits in terms of competitive differentiation or service improvement for end users.

Such an opportunity for adjustment would reduce the risks of intervention by this new regulatory arm of CADE and would, once again, serve as a reminder that the potential benefits of a practice to the market and to consumers should always be part of any antitrust analysis — whether in digital or physical channels.

[1] MARANHÃO, Juliano. The New York Times versus OpenAI: The Crisis of Journalism and Copyright Protection in the Face of Generative Artificial Intelligences. JOTA, January 13, 2024. Available at: https://www.jota.info/opiniao-e-analise/artigos/the-new-york-times-versus-openai. Accessed on September 29, 2025.

[2] EUROPEAN COMMISSION; COMPETITION & MARKETS AUTHORITY; DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE; FEDERAL TRADE COMMISSION. Joint Statement on Competition in Generative AI Foundation Models and AI Products. July 23, 2024. Available at: https://competition-policy.ec.europa.eu/about/news/joint-statement-competition-generative-ai-foundation-models-and-ai-products-2024-07-23_en. Accessed on September 29, 2025.

[3] LEGAL WINGS INSTITUTE. Competition in AI Markets – Full Report (Forthcoming). September 2025.

[4] ADMINISTRATIVE COUNCIL FOR ECONOMIC DEFENSE (CADE). Merger Review Procedures No. 08700.005961/2024-19 (regarding the relationship between Microsoft and Mistral AI); 08700.005638/2024-37 (regarding the relationship between Google and Character.AI); 08700.005962/2024-55 (regarding the relationship between Amazon and Anthropic).

[5] MARANHÃO, Juliano. AI and the Risk of Fear: The Risk Seems Inadvertent When Authorities React Impulsively to Technological Alarms. JOTA, October 28, 2024. Available at: https://www.jota.info/opiniao-e-analise/artigos/ia-e-o-risco-do-medo. Accessed on September 29, 2025.

[6] MARANHÃO, Juliano et al. Competition in AI Markets – Full Report. LEGAL WINGS INSTITUTE, September 2025. (https://www.legalwings.com.br/_files/ugd/df689d_5bc2e9363a0f42d7953305b98d88c9c3.pdf)