The Copyright Mill in Generative AI Training

*Originally published in Jota.

**This is an AI-powered machine translation of the original text in Portuguese

Is there copyright infringement in using works to train generative artificial intelligence models without prior authorization? This is one of the most controversial legal questions in the field of copyright and AI regulation.

Several lawsuits have been filed in recent years, in Brazil and abroad, seeking copyright damages against developers of generative AI across different types of content, such as text, audio, and images. Few cases have reached a decision, and some have resulted in settlements without a ruling on the merits.[1]

Bill 2338/2023, which proposes AI regulation in Brazil, imposes on developers obligations to identify protected works in training datasets, manage consent, and compensate authors. Even if it does not say so explicitly, it practically presupposes that copyright applies to this computational use of protected works.

But is this presupposition correct?

Brazil’s Copyright Act (Law 9,610/1998) states that “the use of the work depends on the author’s prior and express authorization” (art. 29, caput) for its partial or total reproduction (I), its “inclusion in a database” (IX), or “storage in a computer” and “any other forms of use existing or yet to be invented” (X).

This provision seems broad enough to imply protection, but what often goes unnoticed in a cursory reading is that Article 29 refers to the use of the copyrighted work. And here lies a crucial technical subtlety.

The object of copyright protection—the artistic or literary work—is the author’s individual expression of an idea, materialized in a particular medium. This individualized expression forms the content of a communication between author and public[2] through the work, a communication that presupposes the possibility of apprehending its meaning.[3]

Thus, the “use” referred to in copyright legislation is the expressive use of the individual work, with semantic content, communicated or made available to the public. If, in the analog realm, the use of data materialized in a given medium necessarily entails expressive use of the work, the same does not hold for the use of the digital data corresponding to the work.

For human perception, the detection of analog data and the extraction of meaning are immediate. When a person competent in a language identifies a sequence of characters, they grasp its meaning within a grammar. When they perceive sound-wave amplitudes or vibrations, they recognize sounds, voices, etc., which produce understanding or emotions. When they face a visual work, they immediately perceive colors, shapes, and depth that allow comprehension and evoke sensations.

Digital perception and understanding of texts, audio, images, and video, however, are mediated by the machine. Analog content is encoded (embedding) and may undergo different forms of logical processing, only then to be decoded and projected for human perception. A computer does not understand, see, hear, or perceive continuous movement.

Basically, the computer represents the world in numbers and processes them syntactically, while the hardware, together with devices, decodes bits—converting numbers into physical signals so that the human brain may perceive them and assign meaning.

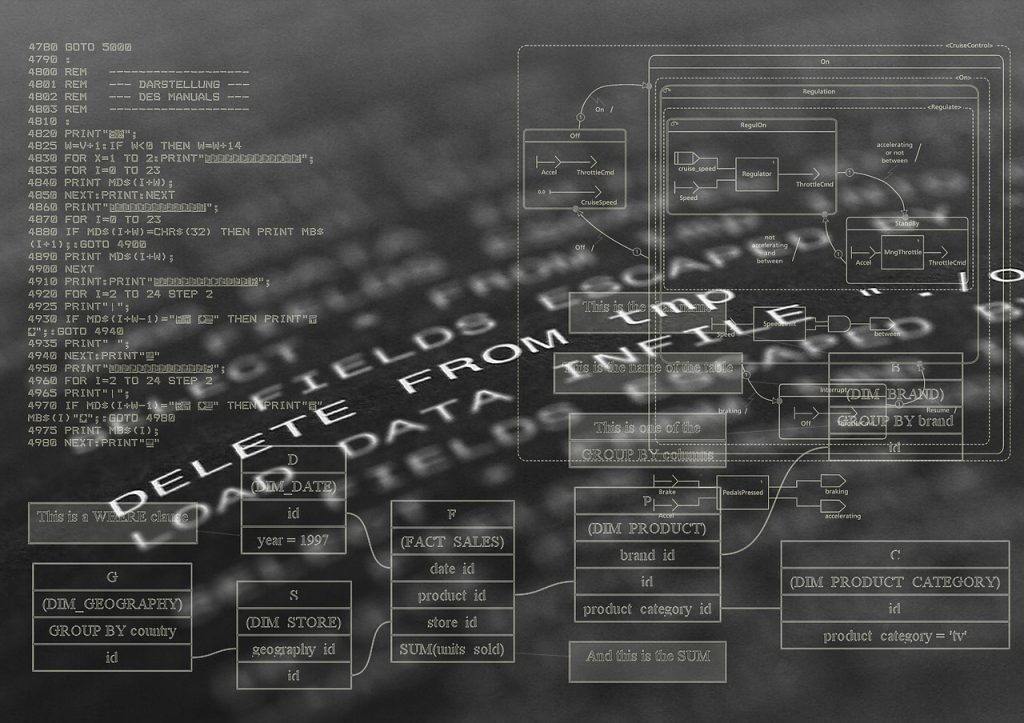

Between encoding into bits and decoding, logical processing consists of a series of syntactic manipulations of binary numbers, unintelligible to humans. And when a work is digitized or created digitally, its corresponding digital data may be processed to project the work in its individuality for human perception, but they may also be processed for other purposes.

For example, digital data corresponding to artistic and literary works may undergo “compression” processes to improve storage efficiency, be copied for backup purposes, transferred to third-party databases for malware scanning, or have their databases restructured to improve access control.

In these situations, the digital data corresponding to the work are manipulated without any intention of establishing author-to-public communication of individualized meaning, and therefore copyright protection is not implicated. Note, for example, that the Brazilian Software Law (Law 9,609/1998) explicitly exempts backup copies in its Article 6, item I.

As analyzed in depth in the report Generative Artificial Intelligence: Copyright Training, by the Legal Wings Institute,[4] the use of digital data corresponding to protected works for training generative AI models is simply another form of logical-computational processing that does not involve expressive use of the individual work.

First, because in digitization we are dealing only with the manipulation of binary numbers, without any expression of meaning or communication of the work between author and public.

Second, because the result of the logical processing involved in the training of a general-purpose generative AI model is a mathematical (statistical) representation of the aggregate of digitized data, corresponding to a set of various works. This representation captures general patterns, concepts, and styles, encoded in parameters and weights, which do not reproduce or store the individual aspects of each digitized work used in training,[5] but which may be used—during inference by generative AI systems based on that model—to generate new content from those parameters and weights.

Thus, in the construction of the generative AI model itself, there is no possibility of communicating meaning, nor is the digital representation of any individual work stored or memorized. For this reason, there is no object subject to copyright protection.

U.S. courts have applied the “fair use” doctrine to point out the absence of expressive use of the work. In Bartz v. Anthropic, for example, the court recognized that training Claude is “transformative use,” because it results in a product that creates content and does not produce copies.[6]

In the case brought by authors against Meta, although transformative use was recognized, the court acknowledged that generative AI systems may compete with human production; however, it required proof that the exploitation of the specific copyrighted work had been limited.

Another relevant precedent is Vanderhye v. iParadigm (2009),[7] in which the court found no copyright infringement in the development of the Turnitin plagiarism-detection software, because the computational verification process “bore no relation to its expressive content.”

A series of similar cases involving the indexing of web documents or the indexing of book content reached the same conclusion. In fact, more than simply limiting the exercise of copyright, these precedents—through their reasoning—end up revealing genuine exceptions to its application.

This same conclusion of absent expressive use or reproduction of the work itself formed the basis of a recent decision by the U.K. Intellectual Property Court in Getty Images v. Stable Diffusion.[8] According to the court, although the model’s parameters and weights are altered through exposure to individual works, the model does not store those works, and therefore does not, in itself, produce infringing copies.

Thus, there is a fundamental distinction between computational uses of works for “the robot’s eyes” and uses for “the human’s eyes.”[9] The crucial feature for copyright protection is whether the data processing will or will not result in the expressivity of the meaning of the individually considered work. Otherwise, to use SAG’s apt metaphor, there is merely a “data mill” engaged in pure computational processing.[10]

And in the training of generative AI models, we are indeed dealing with a mill of digitized data corresponding to copyrighted works, intended only for the robot’s eyes—that is, for the robot to extract patterns that enable it to produce, and assist humans in producing, new works, rather than copying works used in training. Specifically in this type of use, there is no copyright protection to be applied.

[1] BRUELL, Alexandra. Amazon to Pay New York Times at Least $20 Million a Year in AI Deal. Wall Street Journal, July 2025. Available at: https://www.wsj.com/business/media/amazon-to-pay-new-york-times-at-least-20-million-a-year-in-ai-deal-66db8503. BLOOMBERG

[2] CÂNDIDO, Antônio. Literature and Society. Editora Nacional, São Paulo, 1965, pp. 44–45.

[3] ASCENSÃO, José de Oliveira. Copyright Law. 3rd ed. Rio de Janeiro: Renovar, 2007, pp. 32–33.

[4] MARANHÃO, Juliano. Generative Artificial Intelligence: Training and Copyright. Legal Wings Institute, 2025. Available at: https://www.legalwings.com.br/_files/ugd/df689d_a82dced9b9934feeaf836bd95212cbf4.pdf. Accessed: 27 Nov. 2025.

[5] GUADAMUZ, Andrés. A Scanner Darkly: Copyright Liability and Exceptions in Artificial Intelligence Inputs and Outputs. Internet Policy Review, vol. 12, no. 1, 2023. Available at: https://policyreview.info/articles/secure/1771. Accessed: 27 Oct. 2025.

[6] UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT, NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA. Case 3:24-cv-05417-WHA, Document 231, Filed 06/23/25 (Order on Fair Use). Available at: https://admin.bakerlaw.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/ECF-231-Order-on-Fair-Use.pdf. Accessed: 26 Oct. 2025.

[7] A.V. ex rel. Vanderhye v. iParadigms, LLC, 562 F.3d 630 (4th Cir. 2009).

[8] Getty Images (US) Inc & Ors v. Stability AI Ltd [2025] EWHC 2863 (Ch), Case No. IL-2023-000007 (High Court of Justice, Business and Property Courts of England and Wales, Intellectual Property List (ChD), Mrs Justice Joanna Smith DBE, 4 November 2025).

[9] GRIMMELMAN, James. Copyright for Literate Robots. Iowa Law Review, vol. 101, 2016, p. 657. University of Maryland Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2015-16. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2606731.

[10] SAG, M. Orphan Works as Grist for the Data Mill. Berkeley Technology Law Journal, vol. 27, pp. 1503–1550, 2012.